Music Interview with J. Willgoose, Esq., Public Service Broadcasting (pt. 1)

“I spent a lot of time in libraries – as you do with all the great rock ’n’ roll albums,” quipped Public Service Broadcasting’s bandleader when speaking about the research behind their records. With archival voices and broadcasts, the British band resurrects defining moments of history. Thierry Somers speaks with J. Willgoose, Esq., about his protectiveness over working on new material, making The Last Flight – their album about Amelia Earhart’s doomed journey – and the band’s eccentric stage attire: bow ties and corduroy suits.

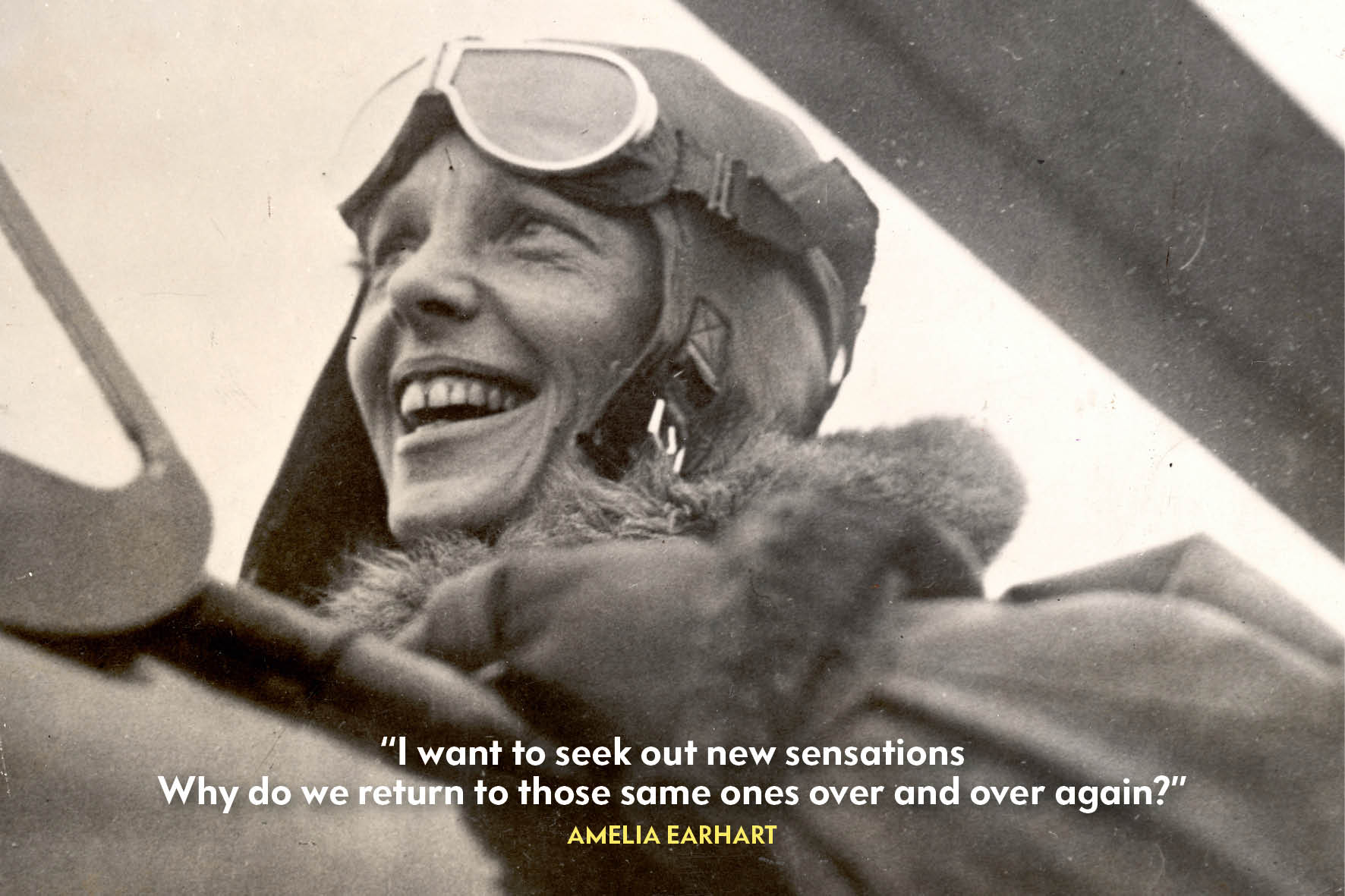

What would it feel like to fly an airplane? For many, an experience that remains out of reach – including the author of this article – but when you listen to Arabian Flight by Public Service Broadcasting, you feel as if you’ve come close. The track belongs to The Last Flight, an album about Amelia Earhart’s attempt to become the first female aviator to fly around the world in 1937.

The song recounts the part of her most difficult journey, flying along the edge of the Arabian Peninsula, and being obliged to fly around certain regions where flying is forbidden. It is imaginative songwriting at its best. It opens with a darbuka drum setting an Arabian atmosphere, followed by two and a half minutes of steady, melancholic rhythm played by guitar, bass, and drums, joined by an orchestra, creating a vast panorama of infinite space. This repetition conveys the experience of piloting an aircraft – the steady hum and rhythm of an engine holding you aloft against the sky. Throughout, we hear Earhart’s voice from the cockpit, marvelling: “Perhaps the greatest joy of flying is the magnificence of the view. The passenger seat gets to see the whole world.”

The song offers listeners a vivid sense of what it feels like to be behind the controls – the freedom of flight, the exhilaration of soaring high above the landscape, with the world unfolding beneath your wings.

A Different Kind of Love is another song from the album that sparks the imagination. It features a reenacted telephone conversation between Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, ending with the words: “See you soon.” Ordinary words, yet heavy with fate. What follows is Howland, named after the island Earhart never reached, a track about her dramatic and mysterious disappearance. Her distressed voice vanishes into the airwaves, followed by a minute of silence that is broken by the sound of squealing birds and the sea washing ashore.

A Different Kind of Love is another song from the album that sparks the imagination. It features a reenacted telephone conversation between Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, ending with the words: “See you soon.” Ordinary words, yet heavy with fate. What follows is Howland, named after the island Earhart never reached, a track about her dramatic and mysterious disappearance. Her distressed voice vanishes into the airwaves, followed by a minute of silence that is broken by the sound of squealing birds and the sea washing ashore.

Willgoose employs cinematic storytelling techniques to build narrative and sound design, using them in a layered, subtle way so that with each listen, another detail surfaces – proving wrong a critic who once questioned their replay value.

Each album is centered around a theme. Not just music, but an expedition – into space, into the mountains, onto the sea, or down into the earth itself. The Race for Space. Everest. White Star Liner. Every Valley. What unites them is the use of archival voices and broadcasts, born from Willgoose’s dissatisfaction with his own singing voice and reluctance to share it with an audience. My first question to him, during our online video call, was whether he felt he had managed to turn a limitation into an advantage.

J Willgoose, Esq: I don’t think that’s really for me to say about us, but it is what many of my favourite musicians have done. Take Lindsey Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac, for example. His finger-picking style isn’t traditional, but the emotion he draws from his guitar, and the way he channels it into a rock band context, is extraordinary. I have plenty of limitations myself, so it would be nice if I could turn one or two of them into strengths as well [laughs].

200%: How did you come up with the idea of using archival voices and samples?

JW: I was just playing around. I think an often underrated part of making music is playing. There’s a reason it’s called playing music. You can study it, but when you actually perform or write, you need to keep a playful, creative mindset. I just had my ears open and tried different things. I have been in numerous bands before, but nothing really worked. I started experimenting with samples from the British Film Institute, and for some reason, it just clicked and gelled with my limitations. It allowed me to use my imagination to tell stories, to shape something narrative and sound-based. It’s been a great vehicle for me, a strong outlet for my creativity, and I’m grateful to have stumbled across it.

200%: Do you have a certain criterion for choosing a sampled speech and then building an entire album around it?

JW: It’s always the story first. When I’m researching ideas for an album – certainly since The Race for Space onwards – I just read a lot. That gets my mind firing up about the subjects I want to cover, the story I want to tell, and the musical ideas that might accompany it. At the same time, I’ll have bits of music bubbling away in the background, and gradually the structure of the record starts to take shape. That’s when I begin writing and searching for the right source material. But it all really starts with reading. It has to be a story that interests me enough to spend a year or two of my life on.

200%: In an interview with KEXP, you disclosed that you spent quite a bit of time in the library researching the subject of an album. What kind of research do you conduct?

JW: To give you an example, I’m working on the next record now, and I’ve been reading a lot about the main subject, taking loads of notes. I spent time at the British Library, going through books, articles, essays, and criticism. This is not very rock-and-roll. It’s more what an author would do when researching a book, immersing themselves completely in the subject. With Every Valley, I went to the South Wales Miners’ Library to listen to oral interviews that weren’t available anywhere else. They were all on cassette, so I sat there for almost a week listening to tape-recorded interviews, particularly looking for information about the women’s support groups. That research directly fed into the song They Gave Me a Lamp.

200%: Could you give a hint about what the new album is going to be about?

200%: Could you give a hint about what the new album is going to be about?

JW: [turns around] Just checking if I haven’t left anything hanging in the background. No, I can’t [laughs]. I feel very protective of it while the idea is still fragile. I don’t want everyone chipping in, so I keep it close to my chest until it’s ready – strong enough to stand on its own.

Nick Cave described it beautifully when he talked about the early stages of songwriting. He compared it to guarding a candle flame – something fragile that any gust of wind could blow out. He feels very protective of his work in those early stages, and that’s exactly how I feel with ours. I don’t really want to tell anyone about it until then.

200%: You’re as secretive as Christopher Nolan, who prints his scripts on red paper so they can’t be photocopied?

JW: Christopher Nolan, but without the budget [laughs]. The people I trust do know, and I’ve had a few conversations about it. But let’s be honest – not that many people care.

200%: Well, I do.

JW: Oh, thank you [smiles]. When I was working on the White Star Liner EP – four tracks about the Titanic – the BBC announced it ahead of time, while I was still writing the songs. After the announcement, people started getting in touch, saying, “You should look at this, you should consider that.” I know it’s always well-meaning, but I want to do my own thing. I want to find my own way through the subject, without outside influences coming in. That’s why I prefer to keep things under wraps.

200%: But your bandmates are involved in the early stages, aren’t they?

JW: They are, to varying degrees. A few weeks ago, I told them on the tour bus late at night what the new album was about. I think Wrigglesworth, our drummer, had a few [drinks] and couldn’t remember the next morning [laughs], so he had to ask me again. Each of them brings expertise I rely on. JFAbraham contributes on the orchestral side, especially with horns and brass. When I can’t program a certain drumbeat, I’ll call Wrigglesworth in and we’ll work on it together. But when it comes to the writing, structure, and overall imaginative direction, I tend to keep a fairly close hold on that myself.

More to come: In the second part of the interview, J Willgoose discusses his collaborations with This Is The Kit and EERA on the lyrics of The Last Flight album, his reasons for enlisting an actor to voice Amelia Earhart on the album, and the upcoming live tour, including the show at the Barbican with the London Contemporary Orchestra.

Interview written and conducted by Thierry Somers

Photo of the band by Alex Lake / Two Short Days